Customs and Border Protection (CBP) bought data from the online advertising ecosystem to track peoples’ precise movements over time, in a process that often involves siphoning data from ordinary apps like video games, dating services, and fitness trackers, according to an internal Department of Homeland Security (DHS) document obtained by 404 Media.

The document shows in stark terms the power, and potential risk, of online advertising data and how it can be leveraged by government agencies for surveillance purposes. The news comes after Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) purchased similar tools that can monitor the movements of phones in entire neighbourhoods. ICE also recently said in public procurement documents it was interested in sourcing more “Ad Tech” data for its investigations. Following 404 Media’s revelation of that ICE purchase, on Tuesday a group of around 70 lawmakers urged the DHS oversight body to conduct a new investigation into ICE’s location data buying.

This sort of information is a “goldmine for tracking where every person is and what they read, watch, and listen to,” Johnny Ryan, director of the Irish Council for Civil Liberties (ICCL) Enforce, which has closely followed the sale of advertising data, told 404 Media in an email.

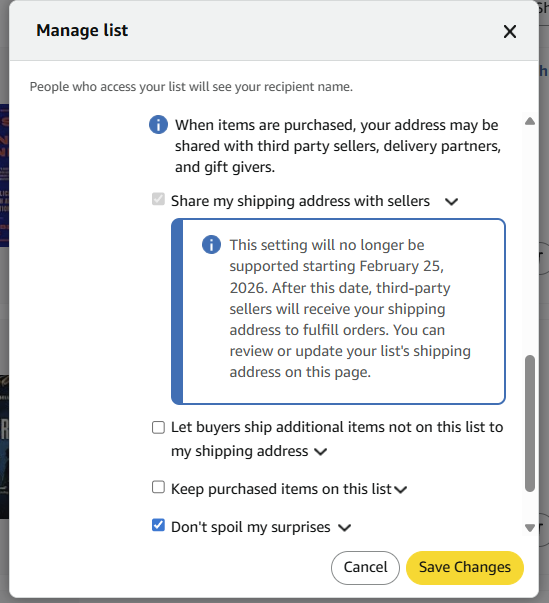

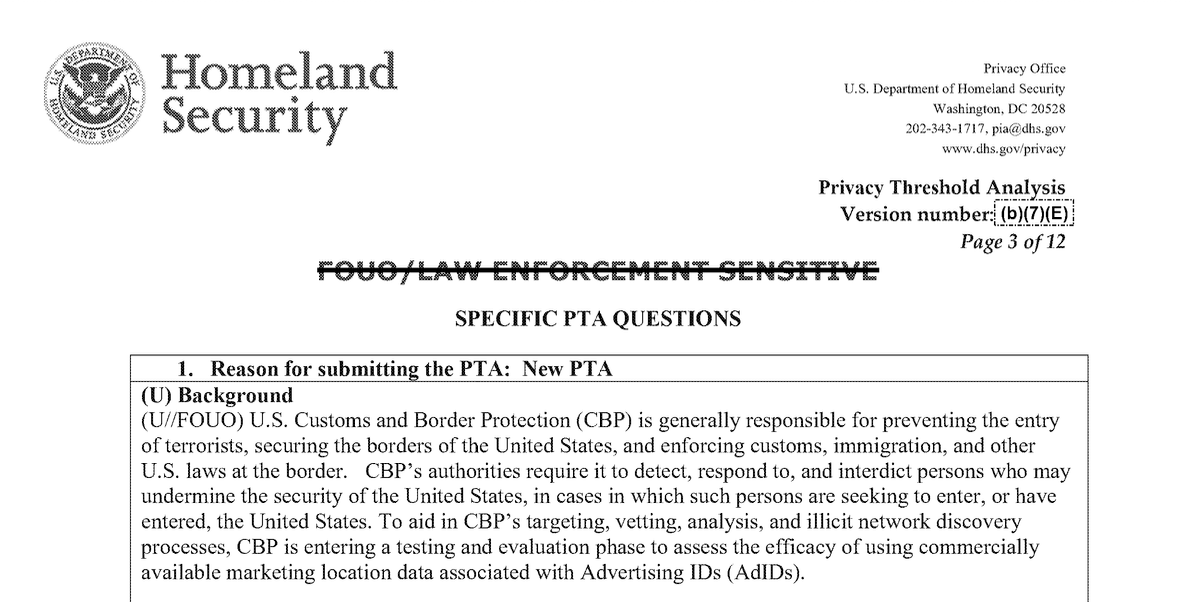

The document 404 Media obtained is the first time CBP has acknowledged the location data it bought came from the advertising industry. Specifically, CBP says the data was in part sourced via real-time bidding, or RTB. Whenever an advertisement is displayed inside an app, a near instantaneous bidding process happens with companies vying to have their advert served to a certain demographic. A side effect of this is that surveillance firms, or rogue advertising companies working on their behalf, can observe this process and siphon information about mobile phones, including their location. All of this is essentially invisible to an ordinary phone user, but happens constantly.

This sort of surveillance can happen through all sorts of innocuous seeming apps, such as video games, news apps, weather trackers, and dating apps. 404 Media has previously linked RTB-based surveillance to games like Candy Crush and Subway Surfers; dating apps Tinder and Grindr; the social network Tumblr, and the popular fitness app MyFitnessPal. In many cases, the app developers themselves are likely unaware they are acting as a conduit for government surveillance because the data collection is not based on any code the app creators have included themselves. The end result is tools that can potentially track hundreds of millions of phones, often without a warrant.

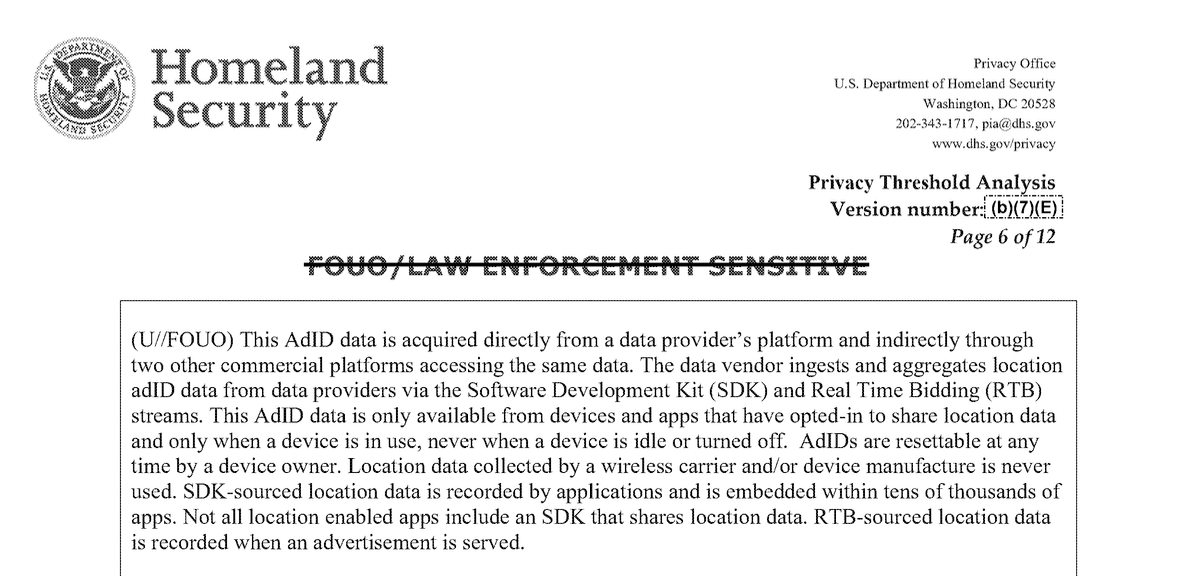

“RTB-sourced location data is recorded when an advertisement is served,” the DHS document reads. The document is a Privacy Threshold Analysis (PTA), a type of record DHS is required to complete when deploying or exploring a new technology. 404 Media obtained it through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request.

The document lays out how the online advertising industry gave birth to this sort of surveillance. Traditionally, marketers used cookies to track consumers’ activities. When those grew less effective due to the rise of smartphones and apps in the 2010s, Apple and Google created Advertising IDs, or AdIDs, that are assigned to each device. These are unique identifiers that, although they don’t contain a person’s phone number or name, still provide a way for the online advertising industry to track devices. As the document says, “this allows app developers to still track and report a device’s consumer activity, to include date/time and locational information, without connecting to or using any personally identifiable information (PII) associated with the device.”

In essence, the AdID acts as the digital glue between a person’s device and their location data, allowing marketers—or a surveillance contractor or DHS—to attribute a set of movements to a specific device. From there, investigators can draw geofences to see all phones at a particular area over a period of time. Many smartphone location data tools then let officials see where else those devices went, potentially revealing where their owners live or work, or other sensitive locations.

“It operates behind the scenes on websites and apps, and it puts everyone at risk. RTB is the world’s biggest data breach,” Ryan added.

CBP acknowledged a request for comment, which asked whether CBP is still using this sort of data, but ultimately did not comment.

The internal document relates to a “pilot” program CBP previously ran from 2019 to 2021, which would “aid in CBP’s targeting, vetting, analysis, and illicit network discovery processes,” it says. The document says the “evaluation will be focused on AdIDs associated with cross border criminal activity and/or activity with an identified terrorist/criminal predicate.”

Although CBP described the move as a pilot, the DHS Office of the Inspector General (OIG) later found both CBP and ICE did not limit themselves to non-operational use. The OIG found that CBP, ICE, and the Secret Service all illegally used the smartphone location data, and found a CBP official used the data to track coworkers with no investigative purpose. CBP and ICE went on to repeatedly purchase access to location data.

In 2020 The Wall Street Journal was first to report on CBP and ICE’s purchase of commercial location data from a vendor called Venntel. The report said ICE used the data to help identify immigrants who were later arrested, and CBP used the data to look for cellphone activity in unusual places, including the stretches of desert on the Mexican border. The FTC later found Venntel illegally sold location data collected without proper consent.

In January, 404 Media reported on material which explained how a similar and more recently ICE-purchased system called Webloc works. It is designed to monitor a city neighborhood or block for mobile phones, then let ICE track the movements of those devices back to their likely homes or other locations. The material did not say how Penlink, the company selling the tool, obtains this location data. But surveillance companies broadly either obtain it through RTB, or small bundles of code called software development kits (SDKs) inserted into ordinary apps.

“By refusing to cut off surveillance companies and sleazy data brokers, Big Tech companies are effectively collaborating with ICE’s lawless campaign of violence and terror. As a result, every internet ad on a website or app could be collecting location data that ICE will use for its next operation,” Senator Ron Wyden told 404 Media in a statement.

“Congress could put a stop to this by passing my bills to ban the government from buying our data and ban tech companies from using surveillance advertising. Until then, the best way for the public to protect themselves is to install ad blockers, disable their phone's advertising ID, and enable the Global Privacy Control in their browser, which 12 states now enforce,” the statement added.

On Tuesday, Wyden, Rep. Adriano Espaillat, and a group of 70 other lawmakers sent a letter to the DHS OIG urging it to once again investigate DHS’s purchase of location data.

“Public reports indicate that ICE has resumed its location data purchases, even though DHS has yet to adopt all of the recommendations from your prior review,” the letter, shared with 404 Media by Wyden’s office, reads. “Your 2023 report noted that there was no DHS-wide policy governing component use of commercial location data. DHS created a commercial data working group in 2022, but as of April 2023, the DHS commercial data working group had yet to issue a policy. Your office recently confirmed that this recommendation remains open.”

The letter says that ICE is “stonewalling” Wyden’s efforts to investigate the Webloc purchase. Wyden’s office requested a briefing on the purchase after 404 Media first revealed it, with that briefing scheduled for February 10. “One day before that briefing was to take place, ICE cancelled it with no explanation and without any offer to reschedule,” the letter reads.

In January ICE posted a request for information—essentially a callout for capable companies to come forward—looking for more access to advertising technology. ICE “is gathering information to better understand how the industry’s commercial Big Data and Ad Tech providers can directly support investigations activities,” the announcement reads. “The Government is seeking to understand the current state of Ad Tech compliant and location data services available to federal investigative and operational entities, considering regulatory constraints and privacy expectations of support investigations activities,” it added.