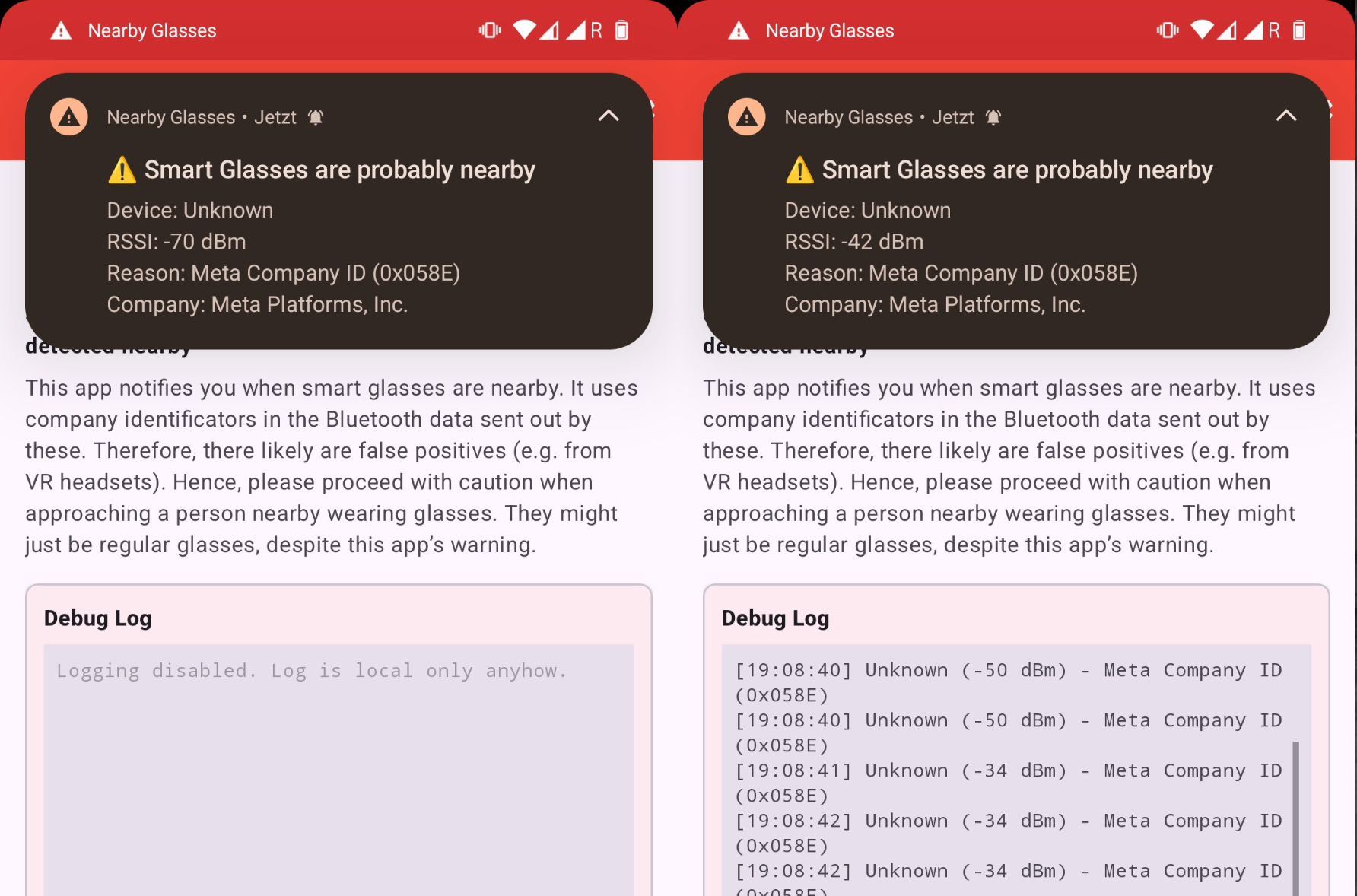

A new hobbyist developed app warns if people nearby may be wearing smart glasses, such as Meta’s Ray-Ban glasses, which stalkers and harassers have repeatedly used to film people without their knowledge or consent. The app scans for smart glasses’ distinctive Bluetooth signatures and sends a push alert if it detects a potential pair of glasses in the local area.

The app comes as companies such as Meta continue to add AI-powered features to their glasses. Earlier this month The New York Times reported Meta was working on adding facial recognition to its smart glasses. “Name Tag,” as the feature is called, would let smart glasses wearers identify people and get information about them from Meta’s AI assistant, the report said.