Amazon is telling people who use its wishlists feature to switch to post office boxes or non-residential delivery addresses if they want to ensure their home addresses remain private, as part of a change in how it processes gifts bought from third-party sellers. The change is especially concerning to many sex workers, influencers and public figures who use Amazon wishlists to receive gifts from fans and clients.

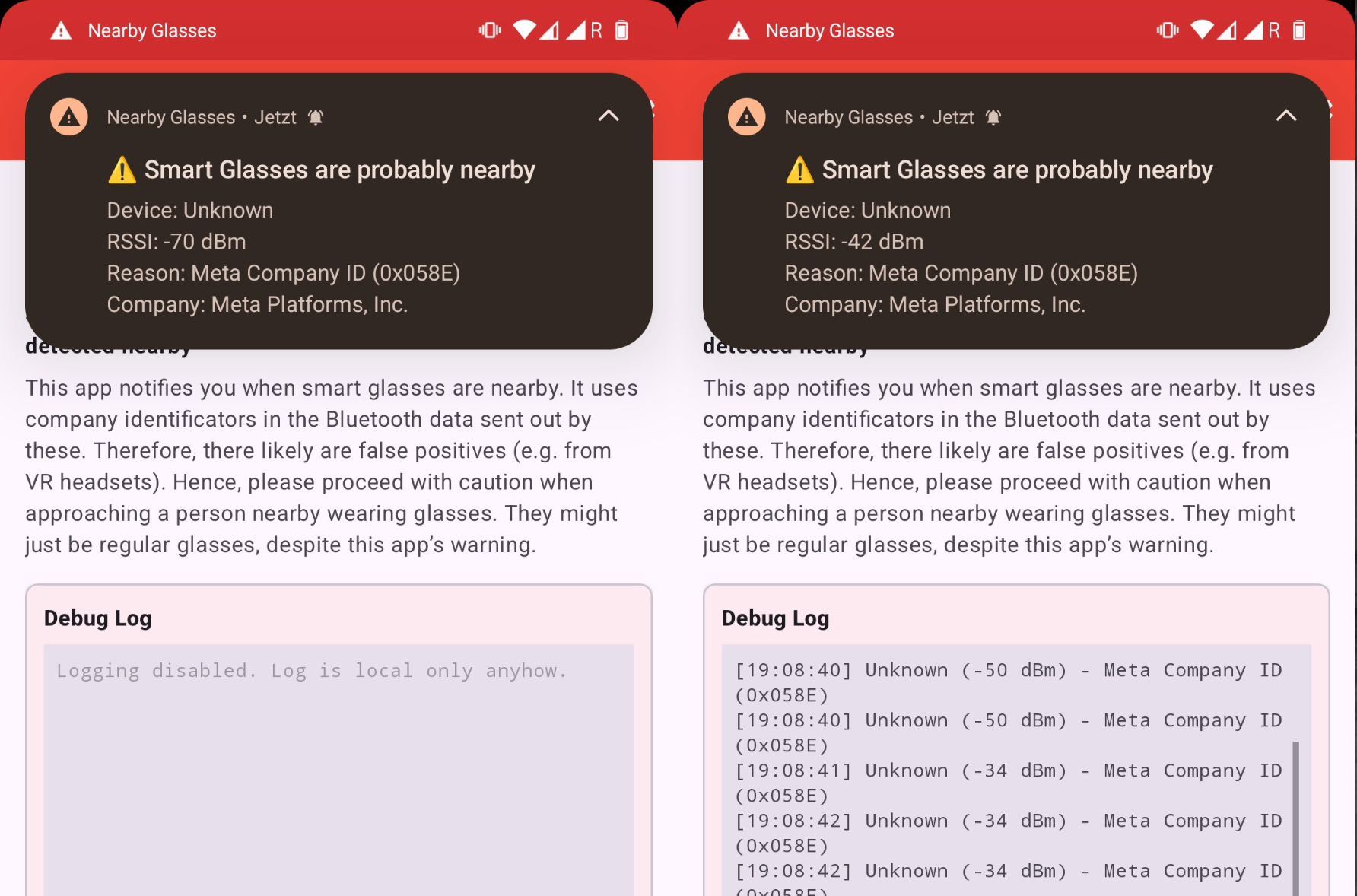

First spotted by adult content creators raising the alarm on social media, the changes open anyone who uses wishlists publicly to increased privacy risk unless they change how they receive packages.

In an email sent to list holders, Amazon said beginning March 25, it will reveal users’ shipping addresses to third-party sellers. The platform added that gift purchasers might end up seeing your address as part of this process, too.

Before this change, the only information visible to sellers and gift purchases was the recipients’ city and state.

“We're writing to inform you about an upcoming change to Amazon Lists. Starting March 25, 2026, we will remove the option to restrict purchases from third-party sellers for list items. When this change takes effect, gift purchasers will be able to purchase items sold by third-party sellers from your lists and your delivery address will be shared with the seller for fulfillment. This change will provide gift purchasers with access to a wider selection of items when shopping from your lists,” Amazon said in the email. “Important note: When gifts are purchased from your shared or public lists, Amazon needs to provide your shipping address to sellers and delivery partners to fulfill these orders. During the delivery process, your address may become visible to gift purchasers through delivery updates and tracking information. To help protect your privacy, we recommend using a PO Box or non-residential address for any list you share with public audiences.”

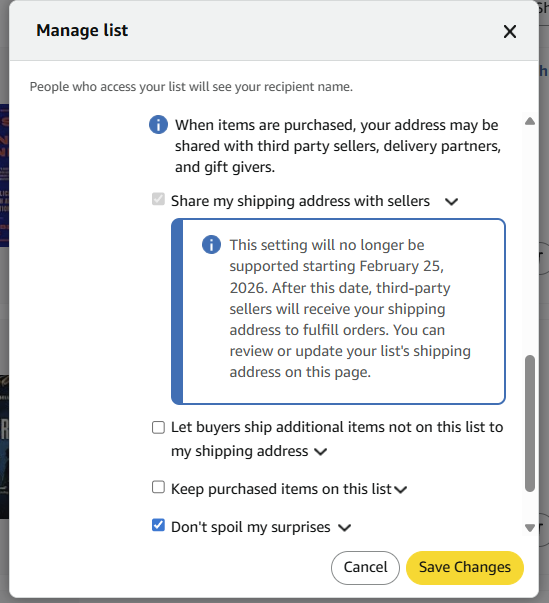

If you have public wishlists, you can manage individual list settings here and select "manage list." From there you can change your list privacy settings to private or shared to limit who has access, or remove your shipping address entirely by selecting "none" from the dropdown menu.

Most of the popular shipping methods in the US, including UPS, Fedex, and the USPS, don’t show full addresses as part of package tracking. But if a third-party seller shares a gift recipient’s home address with a buyer as part of the tracking process, Amazon is saying that’s out of the platform’s control. And some of those delivery services send photos as part of the tracking process for proof of delivery, which could include more information about one’s home or location than they would want a gift sender to see.

“Those who do a range of work where privacy concerns are top of mind would be left to wonder what problem Amazon is solving with this change,” Krystal Davis, an adult content creator who posted about receiving the email from Amazon, told 404 Media. “Those who use these lists as an opportunity to allow fans to show support and offset expenses will lose that option. The alternatives to Amazon wishlist are significantly lacking.”

Many online sex workers use Amazon wishlists to receive gifts from subscribers and fans. It’s a practice that’s gone on for years. Revealing one’s full address to buyers — especially if they don’t realize this change has gone into effect, or missed the email sent by Amazon with the warning to switch to a P.O. box — puts their safety at serious risk. And like so many privacy and security issues that affect sex workers first, anyone could potentially be affected; lots of people use public wishlists who might want to keep their location private, and should consider checking their settings or switching to a non-residential address if they want to maintain that privacy.

Amazon provides conflicting information on when and how this change will go into effect. The email sent to wishlist holders says it will start on March 25, 2026, but as of writing, a notice on the “Manage List” settings page said starting February 25, third party sellers will see users’ shipping addresses. Amazon confirmed to 404 Media that the option to restrict purchases from third-party sellers for list items is being removed on March 25, one month from today.