Primer is The A.V. Club‘s ongoing series of beginners’ guides to pop culture’s most notable subjects: filmmakers, music styles, literary genres, and whatever else interests us—and hopefully you.

The rare modern American auteur to have created and maintained a filmmaking style so recognizable that it’s mimicked, mocked, and admired in equal measure, Wes Anderson has only doubled down on his idiosyncrasies as he’s developed as a director. The more established he becomes as an artist, the more complex and distinct his immediately identifiable comedies become. His recurring key collaborators—from cinematographer Robert Yeoman and music supervisor Randall Poster to production designer Adam Stockhausen and Anderson’s ever-expanding troupe of actors—are some of the industry’s most talented, but they seem to function in Anderson’s films as artisanal translators of impeccable skill. Working in symmetrical harmony, this group fussily arranges a recursive world of paternal letdowns, frustrated geniuses, stifled emotion, dry dialogue, ornate design, and meticulous composition, all of which seems to barely contain the comic chaos and wounded melancholy raging within.

Anderson’s latest film, The Phoenician Scheme, corks up both silliness and depressive sidelong glances at mortality in its ship-in-a-bottle tale about a mysterious mid-century Euro-industrialist. But a trip through the filmmaker’s oeuvre is neither as convoluted as one of his stories-within-stories nor as straightforward as simple chronology. In a career spanning stop-motion animation, sci-fi, heist movies, childhood romance, and frequent midlife crises, it helps to start at the most elemental expressions of Anderson’s larger-than-life schemes and exactly-as-large-as-life deflations. Then you can lose yourself in the beautiful details that color in the nuances of these heightened yet relatable lives.

Wes Anderson 101: Youthful Antics

Fantastic Mr. Fox might seem like a counterintuitive place to start with Wes Anderson. It’s a goofball children’s movie, his first adaptation, his first animation—a talking-animal film from a guy concerned with layered narrative devices, dysfunctional families, and rigid aesthetics. But it’s because Anderson is able to so successfully incorporate his preoccupations into an endearingly silly, sharply written, beautifully animated Roald Dahl tale that they all become the most accessible versions of themselves.

Co-written by Anderson and Noah Baumbach, Fantastic Mr. Fox threads a bad dad into a story filled with petty kids, obsessive needledrops, deadpan humor, autumnal colors, and cute critters who say “cuss” instead of swear words. Its cast also features more than just Anderson’s usual group of actors (like his college roommate/early co-writer Owen Wilson, Jason Schwartzman, Bill Murray, Willem Dafoe, and Adrien Brody). It offers a look into Anderson’s personal life. His younger brother Eric voices Kristofferson. His romantic partner Juman Malouf voices Agnes. Illustrators, co-writers, producers, animation executives, set photographers, and art dealers round out the supporting roles—where so many modern animations stuff their ensemble with flashy names, behind the puppets are those in Anderson’s circle.

One also gets the sense that Anderson found a medium so intimately linked with planning, detail, and effortful production resonant to his creative process. While his second stop-motion film, Isle Of Dogs, loses some of his sensibility in its goofy sci-fi setting and uneasy mix of barking dogs and untranslated Japanese, Fantastic Mr. Fox connects form and function perfectly. As Mr. Fox (George Clooney, in snappy Danny Ocean mode) fails to ignore the call of his wild urges, the ensuing heist comedy encapsulates the kind of antics that result from the efforts of would-be geniuses to corral those around them into elaborate plans that are always on the brink of failure. There’s something self-effacing about a filmmaker returning to this throughline, and it’s never more charming than when delivered by woodland creatures in corduroy suits.

But that theme is established in Anderson’s first two films, the relatively tamped-down ’90s movies Bottle Rocket and Rushmore. The pair also focus on fantasizing dreamers whose bubbles are burst by the disappointingly sensible world around them. Underneath these comedic designs, though, is still the deep well of sadness and self-doubt which provides fuel for his characters’ over-the-top compensations.

Though Anderson’s debut, Bottle Rocket, might initially seem too simple in look and scope to reflect what he would get up to after his career took off, this relatively sparse movie allows his identity (as a striving Texan dreaming big) to come through more clearly than his more elaborate constructions. That might be a boon for those leery of Anderson’s schtick, worried they’ll quickly succumb to an overdose of whimsy. Bottle Rocket still has plenty of whimsy, but it’s scrappy and grounded—less fussy and more in keeping with the chatty ’90s indie boom. It’s even more grounded for me, as the heist attempted by Dignan (co-writer Owen Wilson), Anthony (Luke Wilson), and Bob (Robert Musgrave) partially involves them sticking up a strip-mall bookstore worker played by my former University Of Oklahoma acting teacher.

The small emotional moments cutting through the film’s overcomplicated buffoonery—hallmarks that would continue to disarm audiences in Anderson’s later work—power Bottle Rocket beyond its matching yellow jumpsuits and silly, trendy slacker criminals. It’s not that Dignan ends up in jail after botching every possible aspect of his robbery, but that his shenanigans helped get his partner in crime Anthony back on track after a self-imposed stay at a voluntary psychiatric unit. All the decoration and chatter and silliness serves to ornament a deep ennui, and to flood the senses with the little moments of sweet absurdity that can bring you back from the brink.

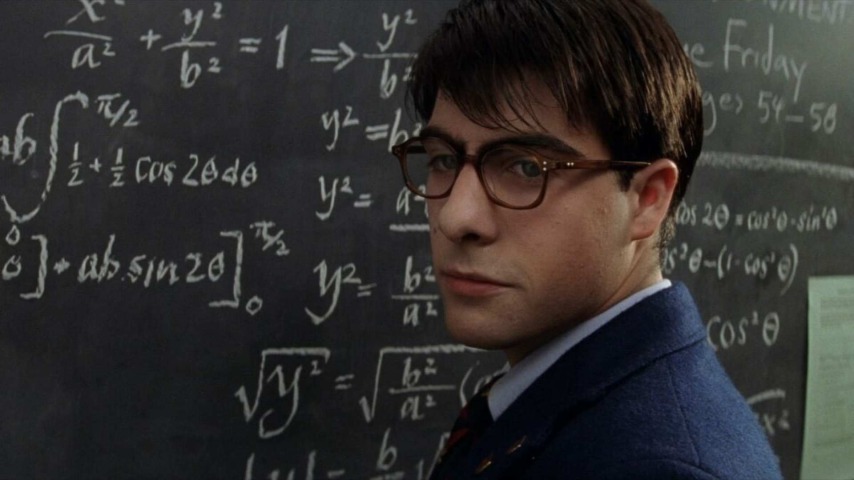

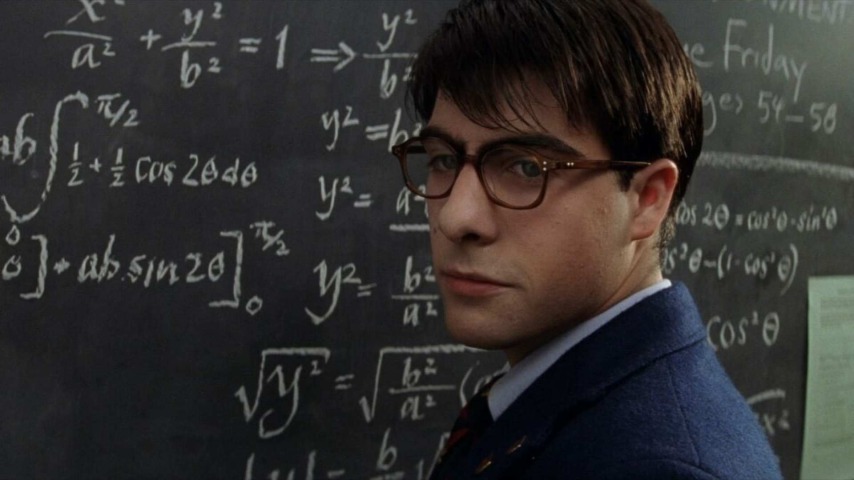

If Bottle Rocket planted the seeds for Anderson’s intensely personal sense of style, Rushmore saw them flourish under his green thumb. Making his wunderkind younger (and more reflective of Anderson’s childhood as an oddball Texas private school kid at St. John’s School, where much of the film was shot) and the person tolerating/humbling him older helped add emotional depth to the romp. It’s not just a maximally stylish movie about the eccentricities of scholarship kid Max Fischer (Jason Schwartzman), but about his aspirational relationship with the wealthy Herman (Bill Murray, whose performance gave his career a shot in the arm). It’s about the ridiculous plays Max puts on, the plans he executes, and the older women he hits on, but all through the lens of a class-conscious, self-conscious coming-of-age story.

This added emotional pain, with just enough autobiography to feel honest, eases you into the over-the-top dialogue, the painstakingly curated soundtrack of ’60s B-sides, and the unabashedly nerdy visual artistry. It’s one of Anderson’s most balanced works, a satisfyingly even blend of anxiety, grief, jealousy, and anarchic slapstick, spread between a precocious mess and his middle-aged foil.

Moonrise Kingdom, just as tight and funny as his earlier work, goes even younger and more tender for its bittersweet summer-camp romance, though the adults fumbling around on its edges are just as pitiable. By isolating its story to a literal island, one partitioned off even further by its runaway sweethearts (Jared Gilman and Kara Hayward), Anderson finds another bubble in which to contain his fantasies. It’s through this world-within-a-world (something else that will become an Anderson go-to), that Moonrise Kingdom also makes accessible another emotional staple in the filmmaker’s repertoire: Sublime, head-over-heels, all-consuming love. This is the film that acts as a perfect springboard from the lightest of Anderson’s younger-skewing films to those completely concerned with the grown children falling apart inside them.

Intermediate Studies: Midlife Crises

The definitive example of Wes Anderson shifting the focus towards those grown children in crisis is The Royal Tenenbaums. Big laughs support a zany-bummer family befitting the film’s clinically depressed cartoonishness—there’s a reason it can unironically drop a track from Charlie Brown Christmas and pull off an aesthetic that includes, as Jesse Hassenger described, “memorably costumed characters with the immediate iconography of a great comic strip.” It’s a film that sums up how midlife crisis moves and looks in an Anderson film: it looks like adolescent crisis, just a little taller, a little more gray around the temples, and a little more run down by life’s increasingly severe consequences.

After ex-prodigies Chas (Ben Stiller), Richie (Luke Wilson), and Margot (Gwyneth Paltrow) grew up to resent their consummate Bad Dad, Royal (Gene Hackman), they’re brought back together by Royal’s allegedly terminal medical diagnosis. On top of a stellar Hackman performance, complex emotions undermine every simplistic feint towards nostalgia; every sweet smile is tinged with bitterness, every big laugh is followed by a line that socks you in the mouth.

The threaded, literary complexity of the family dynamics come across easily, and are far more rewarding than the more straightforward and repetitive baggage lugged around then offloaded by The Darjeeling Limited, perhaps the least of Anderson’s films. Tenenbaums makes Darjeeling‘s brotherly galivant around India feel even more like a tourist trip, a film following a roadmap as familiar as the laminated itineraries provided to that movie’s characters. The siblings resent each other, lament their larger-than-life father’s death, and struggle to grow up without properly, goofily mourning with their last vestiges of childishness. It’s certainly as colorful and well-acted as the rest of Anderson’s work, but it’s the weakest of his crisis comedies—even with Owen Wilson standing in as an Anderson-like control freak.

The film right before Darjeeling, though, The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou, was initially regarded as a trifle yet contains much of the imaginative silliness, ambitious staging, and mature emotions that would go on to define the best of his later work. Henry Selick even provided some of the animation!

It’s also, again, something of an autobiography: A seafaring filmmaker on his way out grapples with iffy reviews, wishy-washy funding, and a dedicated crew that’s just about fed up with his shit. A healthy amount of self-doubt went into the film about the Jacques Cousteau-like Steve Zissou (Bill Murray) and his red-beanied shipmates. Their doomed quest ages up the antics of his younger characters into something more desperate, more pathetic, more relatably grasping for relevance. That gives the undeniably quirk-loaded film a beautifully vulnerable underbelly, making one appreciate its shimmery surface all the more.

Advanced Studies: Passing Down Stories

Though Wes Anderson’s work has long maintained a kinship to literature, with novelistic narratives broken into chapters, his more complex late-period films explicitly become storytelling nesting dolls. The artifice, grown infinitely more intricate over time, becomes another tool for Anderson to put together stories suffused with nostalgic melancholy—either for another time, for another life, or for another way of looking at the world that just used to make more sense. The structure and form now mimic the aesthetic more entirely. It’s all working in tandem, precise color-coded gears ticking away in pleasing harmony to create an illusion of effortlessly well-organized chaos.

The pinnacle of this—in elegance, effervescence, and all-around bisexual cattiness—is The Grand Budapest Hotel. This pink Euro-fable of legendary dandy/concierge M. Gustave (Ralph Fiennes), who takes an apprentice (Tony Revolori) around the same time he gets wrapped up in a fine-art scandal, is dominated by its central comic performance. It’s this dominance that the film attempts to mythologize as the movie goes on: As the film’s plot is retold, recalled, and reframed by the multiple narrative devices and aspect ratios and decades, Gustave becomes larger than life simply by virtue of the way the movie and its characters see him.

There’s a book about him, which was based on an account by an older man, who is the grown lobby boy who once idolized the tiny-mustachioed fop. It helps that Fiennes has never been better, period, but Grand Budapest sets him up structurally to be a superhuman figure worthy of multiple layers of hushed gossip. The ultra-fancy caper collides head-on with continental fascism, zipping along the route of its romantic hero like a pulp novel written by someone as fastidious as Wes Anderson (who, for the first time, wrote this movie alone). Yes, as his films get more densely written, his co-writers drop away—the labyrinthine mapping feels like Anderson in his natural element, how he personally relates to the art of writing.

This then translates to his films more directly dealing with writers and writing. Its look shifting even more than Grand Budapest, The French Dispatch unfurls an anthological triptych like the layout of one of its New Yorker-like periodicals. Its staff reflects on penning their final features, which leap in turn from color to black-and-white, and from full screens to boxy frames.

By turns romantic, political, and madcap, The French Dispatch is homage within homage, with entire genres and specific real-world publishing figures referenced inside the same style Anderson cultivated by devouring French New Wave movies and pieces by James Baldwin. As A.A. Dowd wrote in his A.V. Club review, one of the film’s most literary aspects is that it’s dense enough to benefit from footnotes. It’s one of his only films that feels more like a love letter to its influences than something in service of its diegetic characters, but Anderson makes it undeniably his own.

The same can be said about The Wonderful Story Of Henry Sugar And Three More, which is the collected short films Anderson made for Netflix adapting the Roald Dahl story of the title along with Poison, The Rat Catcher, and The Swan. Aggressively theatrical, these shorts attack form with staccato actors staring down the camera, their breathless line delivery of rapidfire narration directly speaking Dahl’s text. As they speak it, the stagey sets around them come to life, the words becoming worlds. It’s a short story mixed with film told through vaudeville—or a bit like listening to a book on tape at 2x speed and letting your imagination run wild.

Breaking the fourth wall as explicitly and playfully as ever, Anderson uses someone else’s words to do so. Far more experimental than the comparatively primitive Fantastic Fox, these tales toy with the literal and the imaginative, removing key visuals like snakes and rats from stories, but leaving in literary ephemera like the self-evident phrase “I said.” But even amid the semi-cerebral adaptive qualities, one can find streaks of raw emotion. The Rat Catcher turns into Anderson’s creeping Nosferatu while Poison is a thrillingly Hitchcockian lark. The Swan, though, plays with narration in a more quintessentially Andersonian way: To stab the audience in the back with sadness.

Wistfulness, sneaking up out of purposeful intricacy in order to blindside viewers, is key to Asteroid City, which is as good a final destination as Wes Anderson has made so far. (Though he would also make a great Final Destination, now that I think about it.) Asteroid City is a dreamy sci-fi meta-movie. It’s presented as an episode of a ’50s TV show, airing a production of a play by Conrad Earp (Edward Norton) where the actors are playing actors with imperfect understandings of their own characters. Because the film’s own internal narrative instruments are presented as unreliable, every aspect of the movie invites you to think about it in a larger, more abstract way.

As we consider the stranded travelers stuck in a desert town, one better suited for inventive cartoon coyotes and flying saucers than human life, the pandemic quarantine and its emotional aftereffects bubble up. As we consider the actors trying to figure out how to play their roles—-which are, to us at least, the entireties of their lives—-it’s hard not to connect this to the ever-present specter of imposter syndrome running underneath so many of the actions and decisions we’ve faked until we’ve made it. The characters gaze at the stars and their own navels in Asteroid City, protecting their emotions behind stiff veneers like the film protects its vulnerable heart through its nested throwback reference points (The Twilight Zone and TV plays and serialized pulp fiction). But that rawness still comes through, and rewards the thought it provokes: There are few moments in Anderson’s filmography more powerful than the acting class chanting, “You can’t wake up if you don’t fall asleep.” Finding the meaning in joyous, rollicking dreams is a lot like finding the grand truths built into Anderson’s artificial contraptions.