Black Panther is canceled, and workers (once again) suffer the consequences

The post Another Day, Another Round Of Layoffs At EA appeared first on Aftermath.

Black Panther is canceled, and workers (once again) suffer the consequences

The post Another Day, Another Round Of Layoffs At EA appeared first on Aftermath.

Primer is The A.V. Club‘s ongoing series of beginners’ guides to pop culture’s most notable subjects: filmmakers, music styles, literary genres, and whatever else interests us—and hopefully you.

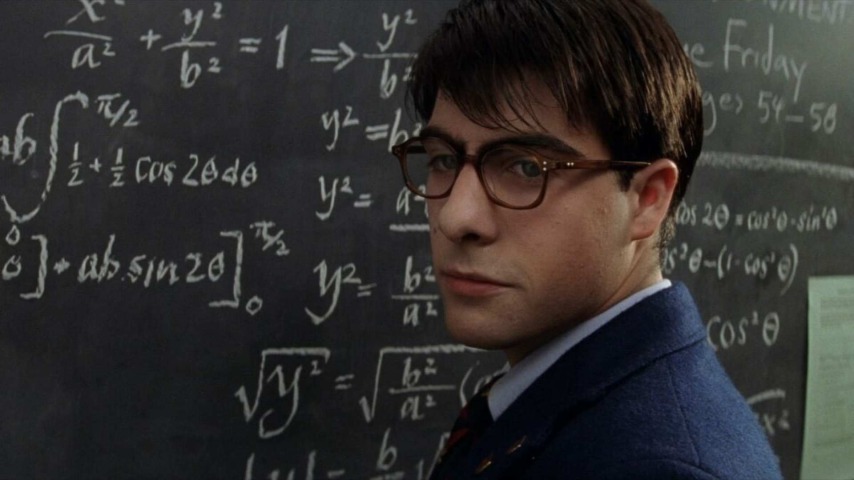

The rare modern American auteur to have created and maintained a filmmaking style so recognizable that it’s mimicked, mocked, and admired in equal measure, Wes Anderson has only doubled down on his idiosyncrasies as he’s developed as a director. The more established he becomes as an artist, the more complex and distinct his immediately identifiable comedies become. His recurring key collaborators—from cinematographer Robert Yeoman and music supervisor Randall Poster to production designer Adam Stockhausen and Anderson’s ever-expanding troupe of actors—are some of the industry’s most talented, but they seem to function in Anderson’s films as artisanal translators of impeccable skill. Working in symmetrical harmony, this group fussily arranges a recursive world of paternal letdowns, frustrated geniuses, stifled emotion, dry dialogue, ornate design, and meticulous composition, all of which seems to barely contain the comic chaos and wounded melancholy raging within.

Anderson’s latest film, The Phoenician Scheme, corks up both silliness and depressive sidelong glances at mortality in its ship-in-a-bottle tale about a mysterious mid-century Euro-industrialist. But a trip through the filmmaker’s oeuvre is neither as convoluted as one of his stories-within-stories nor as straightforward as simple chronology. In a career spanning stop-motion animation, sci-fi, heist movies, childhood romance, and frequent midlife crises, it helps to start at the most elemental expressions of Anderson’s larger-than-life schemes and exactly-as-large-as-life deflations. Then you can lose yourself in the beautiful details that color in the nuances of these heightened yet relatable lives.

Fantastic Mr. Fox might seem like a counterintuitive place to start with Wes Anderson. It’s a goofball children’s movie, his first adaptation, his first animation—a talking-animal film from a guy concerned with layered narrative devices, dysfunctional families, and rigid aesthetics. But it’s because Anderson is able to so successfully incorporate his preoccupations into an endearingly silly, sharply written, beautifully animated Roald Dahl tale that they all become the most accessible versions of themselves.

Co-written by Anderson and Noah Baumbach, Fantastic Mr. Fox threads a bad dad into a story filled with petty kids, obsessive needledrops, deadpan humor, autumnal colors, and cute critters who say “cuss” instead of swear words. Its cast also features more than just Anderson’s usual group of actors (like his college roommate/early co-writer Owen Wilson, Jason Schwartzman, Bill Murray, Willem Dafoe, and Adrien Brody). It offers a look into Anderson’s personal life. His younger brother Eric voices Kristofferson. His romantic partner Juman Malouf voices Agnes. Illustrators, co-writers, producers, animation executives, set photographers, and art dealers round out the supporting roles—where so many modern animations stuff their ensemble with flashy names, behind the puppets are those in Anderson’s circle.

One also gets the sense that Anderson found a medium so intimately linked with planning, detail, and effortful production resonant to his creative process. While his second stop-motion film, Isle Of Dogs, loses some of his sensibility in its goofy sci-fi setting and uneasy mix of barking dogs and untranslated Japanese, Fantastic Mr. Fox connects form and function perfectly. As Mr. Fox (George Clooney, in snappy Danny Ocean mode) fails to ignore the call of his wild urges, the ensuing heist comedy encapsulates the kind of antics that result from the efforts of would-be geniuses to corral those around them into elaborate plans that are always on the brink of failure. There’s something self-effacing about a filmmaker returning to this throughline, and it’s never more charming than when delivered by woodland creatures in corduroy suits.

But that theme is established in Anderson’s first two films, the relatively tamped-down ’90s movies Bottle Rocket and Rushmore. The pair also focus on fantasizing dreamers whose bubbles are burst by the disappointingly sensible world around them. Underneath these comedic designs, though, is still the deep well of sadness and self-doubt which provides fuel for his characters’ over-the-top compensations.

Though Anderson’s debut, Bottle Rocket, might initially seem too simple in look and scope to reflect what he would get up to after his career took off, this relatively sparse movie allows his identity (as a striving Texan dreaming big) to come through more clearly than his more elaborate constructions. That might be a boon for those leery of Anderson’s schtick, worried they’ll quickly succumb to an overdose of whimsy. Bottle Rocket still has plenty of whimsy, but it’s scrappy and grounded—less fussy and more in keeping with the chatty ’90s indie boom. It’s even more grounded for me, as the heist attempted by Dignan (co-writer Owen Wilson), Anthony (Luke Wilson), and Bob (Robert Musgrave) partially involves them sticking up a strip-mall bookstore worker played by my former University Of Oklahoma acting teacher.

The small emotional moments cutting through the film’s overcomplicated buffoonery—hallmarks that would continue to disarm audiences in Anderson’s later work—power Bottle Rocket beyond its matching yellow jumpsuits and silly, trendy slacker criminals. It’s not that Dignan ends up in jail after botching every possible aspect of his robbery, but that his shenanigans helped get his partner in crime Anthony back on track after a self-imposed stay at a voluntary psychiatric unit. All the decoration and chatter and silliness serves to ornament a deep ennui, and to flood the senses with the little moments of sweet absurdity that can bring you back from the brink.

Data from a license plate-scanning tool that is primarily marketed as a surveillance solution for small towns to combat crimes like car jackings or finding missing people is being used by ICE, according to data reviewed by 404 Media. Local police around the country are performing lookups in Flock’s AI-powered automatic license plate reader (ALPR) system for “immigration” related searches and as part of other ICE investigations, giving federal law enforcement side-door access to a tool that it currently does not have a formal contract for.

The massive trove of lookup data was obtained by researchers who asked to remain anonymous to avoid potential retaliation and shared with 404 Media. It shows more than 4,000 nation and statewide lookups by local and state police done either at the behest of the federal government or as an “informal” favor to federal law enforcement, or with a potential immigration focus, according to statements from police departments and sheriff offices collected by 404 Media. It shows that, while Flock does not have a contract with ICE, the agency sources data from Flock’s cameras by making requests to local law enforcement. The data reviewed by 404 Media was obtained using a public records request from the Danville, Illinois Police Department, and shows the Flock search logs from police departments around the country.

As part of a Flock search, police have to provide a “reason” they are performing the lookup. In the “reason” field for searches of Danville’s cameras, officers from across the U.S. wrote “immigration,” “ICE,” “ICE+ERO,” which is ICE’s Enforcement and Removal Operations, the section that focuses on deportations; “illegal immigration,” “ICE WARRANT,” and other immigration-related reasons. Although lookups mentioning ICE occurred across both the Biden and Trump administrations, all of the lookups that explicitly list “immigration” as their reason were made after Trump was inaugurated, according to the data.

Peter David, the comics writer best known for a revolutionary 12-year run on The Incredible Hulk, has died. A lifelong lover of comic books, David had a hand in expanding and reinvigorating the mythos of the medium’s most famous characters, including Spider-Man, Captain Marvel, and Aquaman, picking up an Eisner Award for his work on Hulk. Following years of health issues, his wife, Kathleen O’Shea David, confirmed David died on Saturday, May 24. She did not provide a cause of death. He was 68.

Falcom was a hot computer and video publisher back in the 1980s and early 1990s, with many of its games getting manga adaptations. Here is a look at a handful of them.

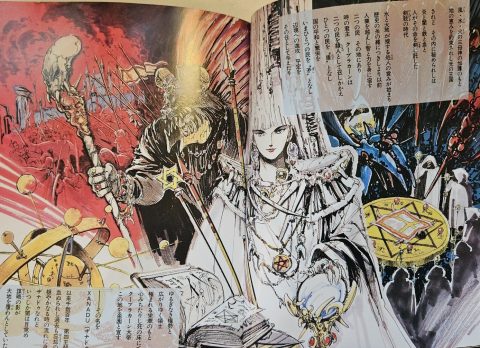

Xanadu

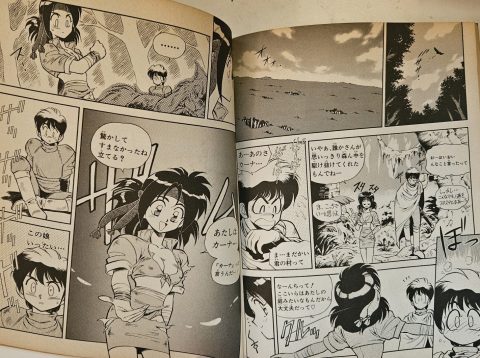

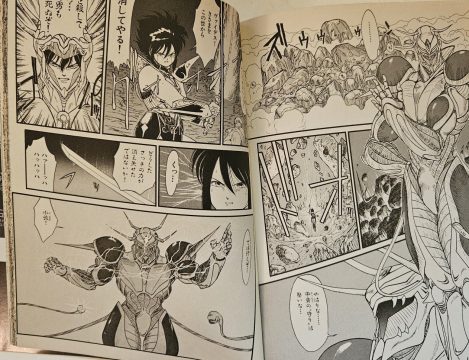

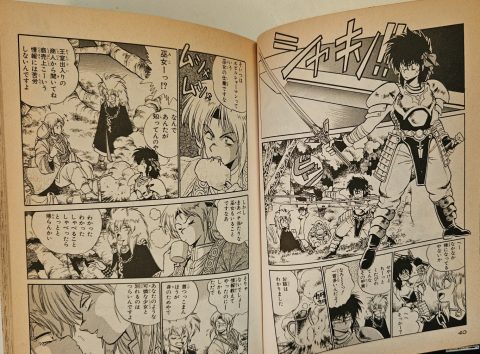

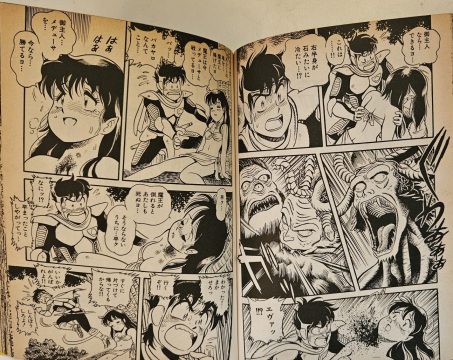

The original Xanadu doesn’t have much of a story beyond the same type you’d find in most 80s CRPGs – explore dungeons, beat up enemies, get stronger, and look for a powerful sword. This obviously wasn’t enough for a manga, so in-house Falcom artist Kazuhiko Tsuzuki created his own. Melding elements of fantasy and sci-fi, the main character is Fieg, a soldier from the near-future who’s zapped into the world of Xanadu, where he becomes embroiled in a magical war. He teams up with the beautiful warrior princess Rieru to fight the evil Reichswar. The fabled Dragon Slayer sword is referenced, and a few of the enemies from the game appear, but otherwise there is no real relation to the game. Nonetheless, Falcom used the manga cover art for certain ports of the Xanadu game. This was also adapted into an anime OVA in 1988, which never officially left Japan.

The title of the manga refers to it as “Xanadu 1”, implying there would be more volumes, but only the first one came out. According to a tweet by Tsuzuki, since he created the manga while he was a salaried employee, he wasn’t entitled to any royalties nor any ownership, so it was canceled after this first volume.

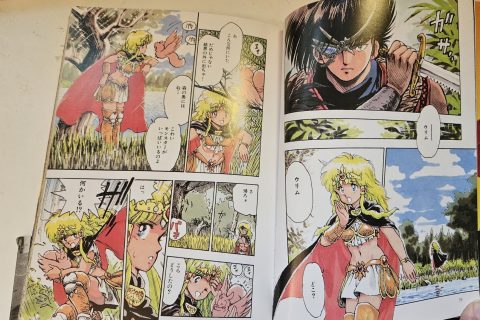

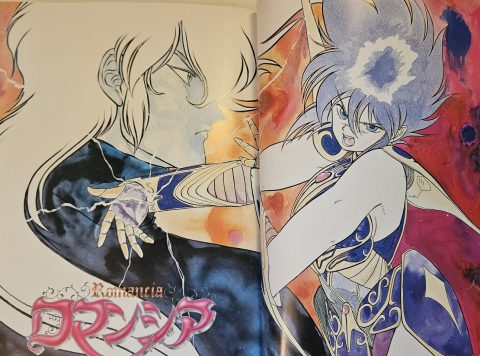

Romancia

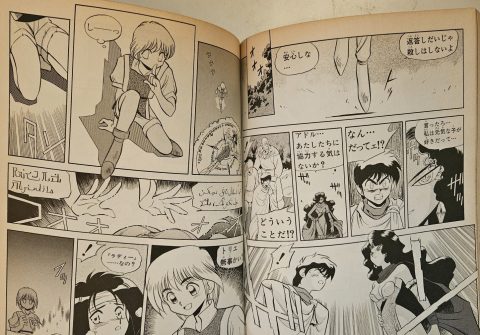

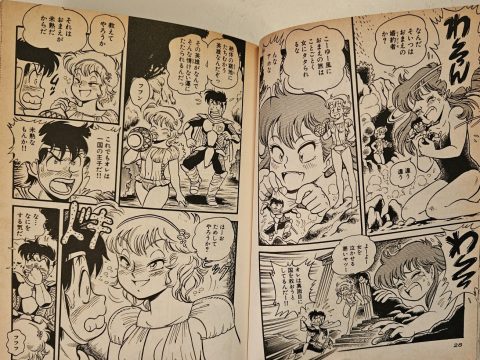

Unlike Xanadu, Romancia actually has characters and a simple story, starring prince Fan Freddie as he saves a neighboring kingdom from monsters and rescues the princess Selina. However, the manga still goes its own direction, in a unique way – rather than focusing on Fan Freddie, as in the game, it instead stars Selina, who’s been upgraded from “kidnapped maiden” to “warrior princess”. This was written by Kenji Terada, an extremely prolific writer across many mediums, who wrote the scenarios for the first three Final Fantasy games as well as the Sega CD SRPG Dark Wizard, among many others. It was illustrated by Hidetomo Tsubura, who also worked on the El Hazard manga. It was also adapted into a drama CD.

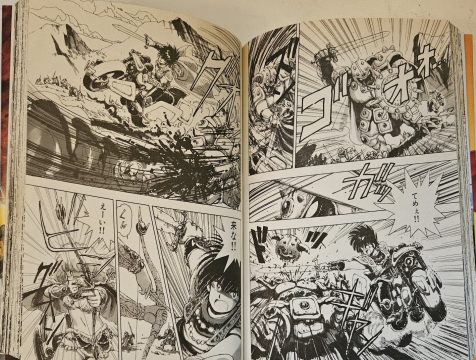

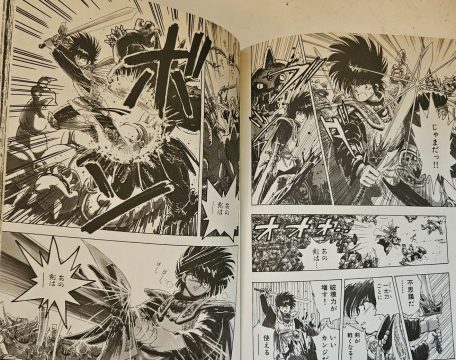

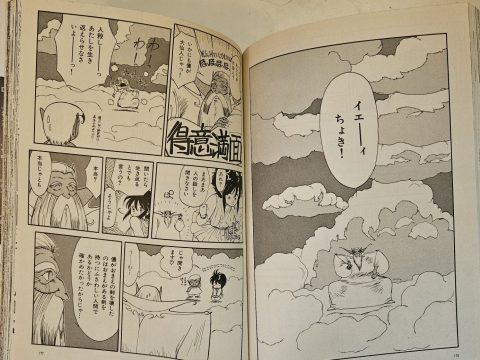

Sorcerian

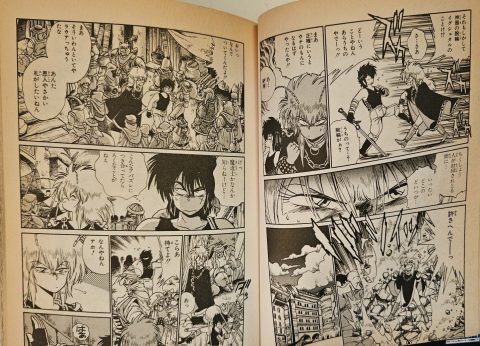

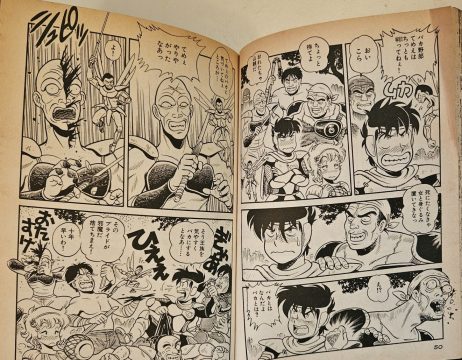

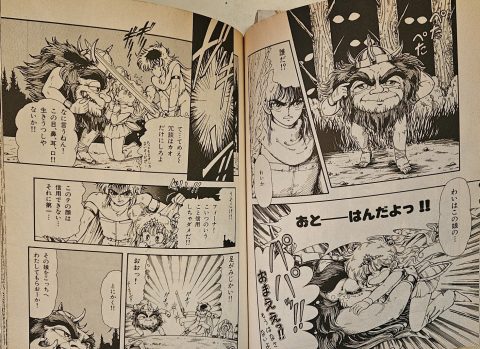

Sorcerian only has a barely overarching story, and instead focuses on mini-scenarios starring player created characters. For its manga adaptations, each scenario was adapted by different authors, giving each a unique style. Pictured here are The Curse of Medusa by Yuusaku Toyoshima and The Gods in the Heavens by Joji Manabe.

Yuusake Toyoshima was famous among the 1980s doujin scene for his anthro art, though none of them appears in his Sorcerian manga. Joji Manabe is most known about Westerners for the manga Outlanders, as well as other fantasy works like Drakuun, Caravan Kid, and Capricorn. As of 2025, he’s been working on Rise of the Outlaw Tamer and His Wild S-Rank Cat Girl.

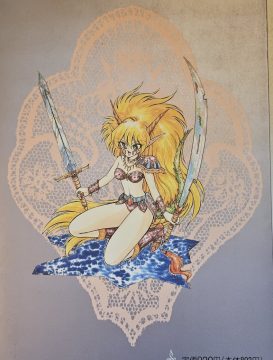

Popful Mail

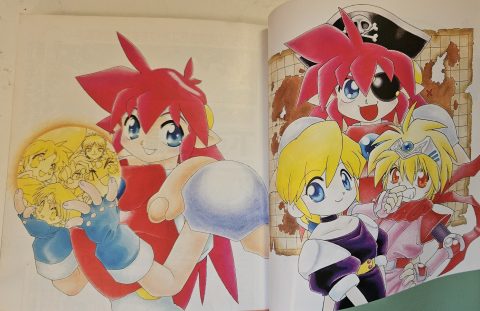

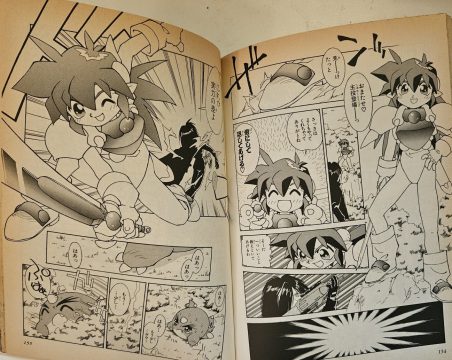

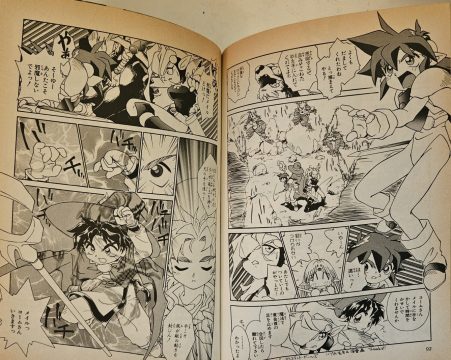

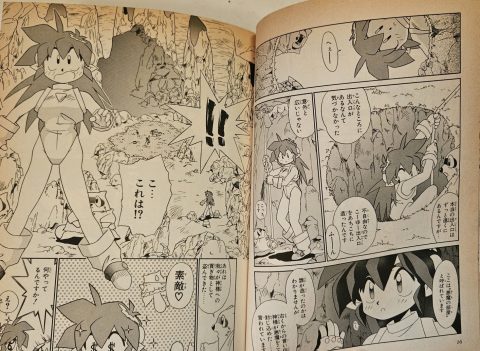

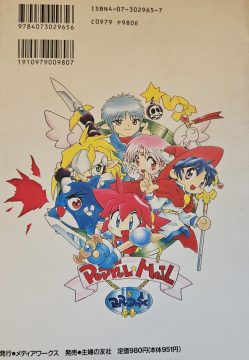

Rather than a video game sequel, Popful Mail received a follow-up in a series of drama CDs released by King Records. These feature Megumi Hayashibara in the title role, which she also played in the Mega CD version. A manga was serialized in Monthly Dengeki Comic Gao and compiled into a single volume. Written and illustrated by Yu Aizaki, these continue along the same line as the drama CDs, with plenty of characters that were only in the drama CDs.

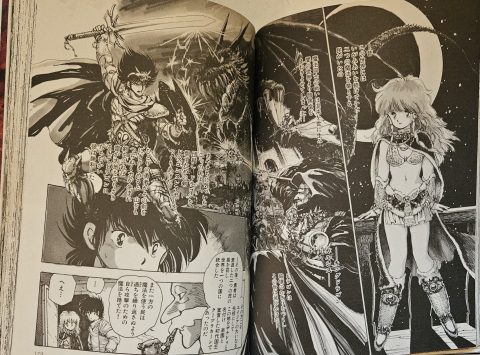

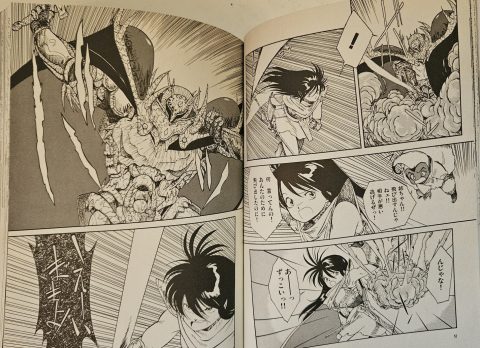

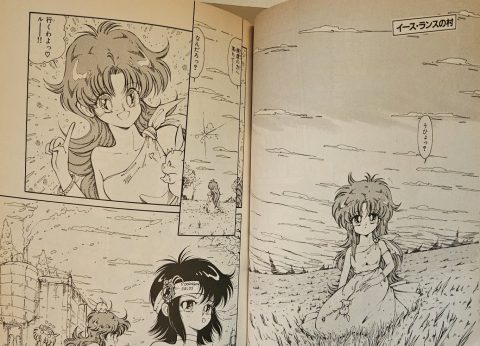

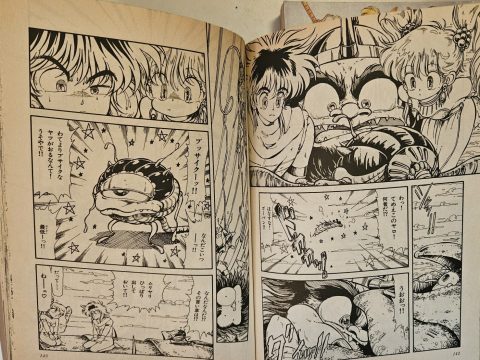

Ys

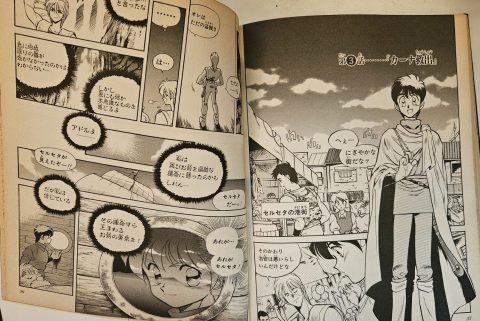

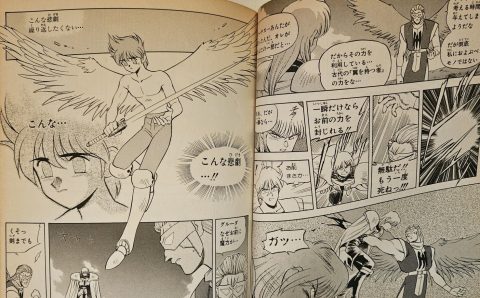

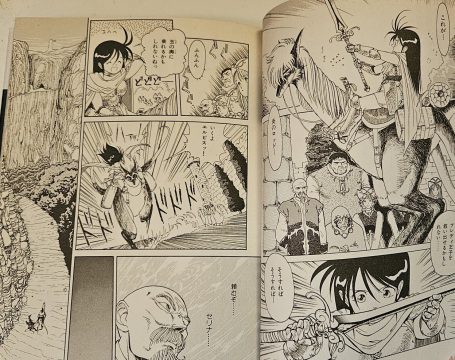

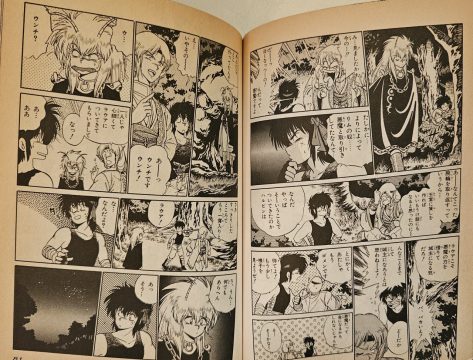

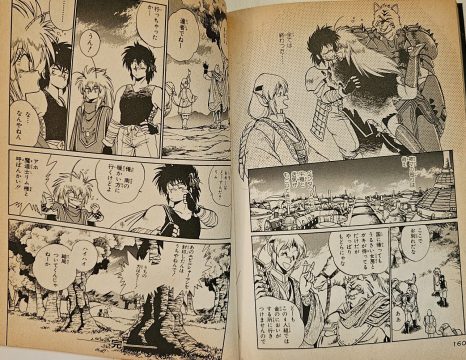

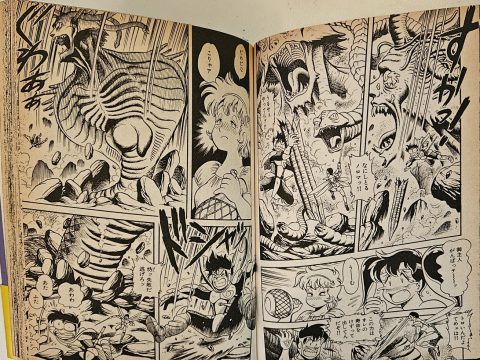

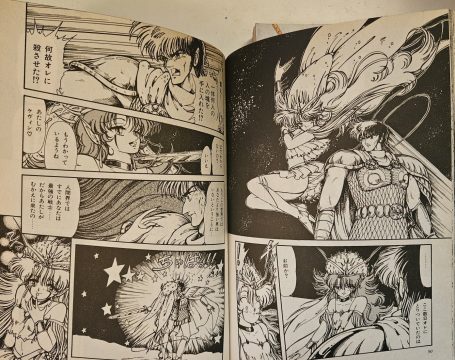

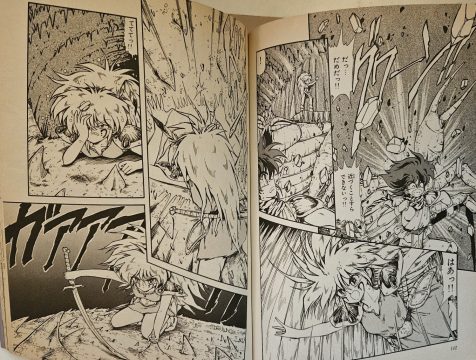

The Ys comic series began in 1989, written and illustrated by Show Hagoromo. He didn’t know much of anything about the game, so he took the basic concept and its characters, and created his own fantasy story, resulting in something wildly different from the games it’s purportedly based on. For starters, Adol finds Feena washed up on a shore, and the two join together to hunt for the books of Ys. Plenty of characters have changed from the game like the old woman Jeva, who is now an attractive younger girl, and Reah now has blond hair instead of matching her twin sister’s blue. There are also plenty of new characters like Maria, a warrior girl from Rance village. Despite not being all that faithful, it was a relatively popular series that originated in Kadokawa Shoten’s Monthly Comptiq magazine (which covered video games, anime, and pretty anime girls) and was compiled into seven volumes.

Hagoromo also did one of the Sorcerian volumes titled The Dark Mage. The characters for these later appeared in the Ys manga, making for a not-entirely-official crossover between Falcom’s series. The character’s adventures continued in another story, The Amazon’s Sword, which is included in the seventh and last volume of the Ys manga. The Dark Mage manga has also been released digitally without the Sorcerian branding.

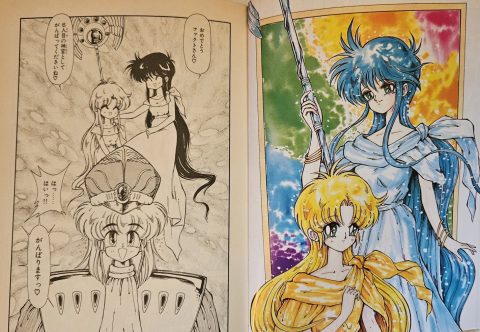

Ys: Mask of the Sun

Illustrated by Hitoshi Okuda (the Tenchi Muyo manga), this is an adaptation of the Super Famicom version Ys IV. The cover credits Kenichi Itoi of Micro Cabin for the story, who was the developer of the game, indicating that this was staying more faithful to its plot compared to Hagoromo’s manga. Obviously the story had to be altered a bit to fit into a single manga volume. There was also an adaptation of Ys V by Akiko Ikegami.

Beyond these, there’s also another Ys manga adaptation by Hidenori Maeda. I haven’t been able to get any copies of these, but all sources point to this also being a much more faithful adaptation of the original two games than Hagoromo’s work.